Introduction

In the historical European crises people have moved, taking their memories as wanted or unwanted packages along. Stories about translocations and their accompanying memories have built up over centuries. What can we learn from stories of our own and of other Europeans for the democratic future of our countries?

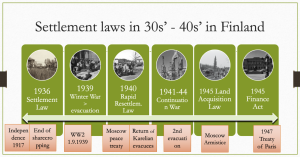

The main topic of this study is the Finnish version of the 2nd World War, which consists of the Winter war and the Continuation war. During this crisis and adaptation period half a Million Finnish citizens living in the eastern part of Finland had to flee their homes because of the occupation made by the Soviet Union. The people were allocated land, which consisted of redistributed land properties from private land-owners and from communal lands. Private owners of the land given to resettlers were monetarily compensated for the loss of real estate. Many of the resettled Karelian people, however, faced harsh discrimination. The Rapid resettlement law was decreed during the Winter war, under a necessity that united the Finnish political parties. It was followed by a Land acquisition law in 1944, which helped the Finnish authorities to resettle the homeless Karelians after the peace treaty of Moscow (a treaty between Russia, Great Britain and Finland). The war veterans received land from the state, as well. Altogether, the people in need of resettlement were nearly 500 000, because the land area handed over to the Soviet Union consisted of more than 12 % of the total surface area of Finland, and its population the same percentage. This means that now, 75 years after the peace treaty, by far most Finns have friends or relatives that are Karelian evacuees or their offspring.

In this study, I refer to sources that convey an overview of the war and resettlements, such as Antti Palomäki’s historical research on settlement, and the mentality historical research of Aapo Roselius and Tuomas Tepora. In his article Tepora (2018) has used as sources wartime mood reports, by which the decision makers were provided with information on how to eliminate major problems. Oral history research complements their studies. I also refer to newspaper articles and autobiographical narratives of evacuees who fled Karelia. In these memoirs, the events of history are manifested as experiences and are often transmitted through emotional memories. According to new research, sources of oral history, such as recollections, have been unduly criticised. They often include nostalgia for the past domicile. Nostalgic remembrance can be considered as based on the past and as a future-oriented community-maintaining practice by which Karelian identity is constructed by gilding a certain place as unchanged and unbroken.

Karelian evacuees and a Russian war prisoner in the fields of Ulriksnäs farm in Ohkola, Mäntsälä, 1941-1944. Photo: Mäntsälän museotoimen valokuvakokoelma, nr. 8512_34. Photographer unknown. User rights: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Emotional historical writing in itself does not make research non-analytical. At its best, it helps the reader in generating associations, insights and empathy. This is how an approximately 80-year-old Karelian woman recalled in her evacuation-history as a contribution to a writing competition:

“In the evening we got the order and the next day I had to leave. I went to do work in the barn, I fed the animals, stroked the animals, caressed them well, and then the tears came into my eyes, I cried lots and lots, we had toiled so much, worked in order to get everything well, and now we had to leave it behind and leave towards the unknown future”.

The decreeing of the land acquisition law was not easy, because it interfered with the private land ownership that had traditionally been highly valued in Finland. The law came into power in June 1945. 1945 and 1946 were the main years of movement and migration. In Finland the housing and land substitution questions of the Karelian evacuees were mainly solved by the end of 1940s’, whereas in other parts of Europe the situation of migrants was dealt with at a slower pace, and there the Marshall Aid offered by the USA came into play, too.

New homesteads were founded and, in towns and cities, building lots were donated, too. Part of the land for resettlement was on woodlands, and the families had to fell the trees in order to make arable land. In order to stabilise living conditions and to heave the production of foodstuffs back on its feet, the laws supported especially the perquisites of agricultural production, and on the other hand, through populating marginal and remote areas workforce for the forestry was guaranteed. A fear existed that unemployment would grow if the population apt for resettlement was not attached to agriculture. Especially the Rural Party believed in residual social policy, and its cornerstones were mainly the free yeomen farmers’ work – even if supported by various forms of assistance.

The time of crisis gave light to agreement despite appeals from interest groups such as land donors. Cities also became responsible for settling the population in the form of plots and subsidised mortgages. In 1945, the Finance Act was enacted to support the migrant population. According to this Finance Act, low-interest loans could be granted to residents in addition to the acquisition of land for clearing and the construction of residential and outbuildings. At the grassroots level, a lot of support work was done, as the neighbours helped each other in a wartime spirit. The returning servicemen also went to the buildings of the war widows to work together. There were no known social boundaries in construction. In the memoirs of the builders, workers and educated people built their houses side by side.

Photo: Karelian mothers and children eating supper in joint lodging premises of Huittinen. HK19890416:12. Finnish Board of Antiquities. CC BY 4.0.